For quite a long time now, I’ve been studying and observing events taking place in Guinea-Bissau, one of Africa’s smallest and most unusual places for the wave of alarming news headlines to be coming out of the tiny West African republic.

Guinea-Bissau, a country only 13,946 square miles with a population of a little over a million, has been desperately poor since fighting a war for its independence from occupation by Portugal’s facist regime in the 1970s.

Lead to independence by the charismatic Amilcar Cabral, who is now seen as an iconic anti-colonial freedom fighter for his bravery and leadership of the leftist revolutionary army, the Partido Africano da Independencia da Guine e Cabo Verde (PAIGC).

The PAIGC, a Soviet and Cuban-funded insurgency, would eventually bring liberation to both Guinea-Bissau and the islands of Cabo Verde. Despite putting up a valiant fight using some of the first tactics of asymmetrical warfare theory, Cabral did not live to see his country’s freedom; he was assassinated in 1973, a year before independence, by Portuguese spies.

After years of colonial subjugation, living with intense aerial bombardment and the attacks of Portuguese troops harassing and destroying the few small towns which prevented the Bissauans from being able to eke out a minor living growing food for themselves and their only export crop, cashew nuts, Guinea-Bissau did not have a good start in the world as an independent nation when the Portuguese capitulated and allowed Guinea-Bissau to become independent in 1974.

Since independence, the country has never found stability. Initially ruled by a military junta, Guinea-Bissau has bounced from leader to leader, with a repetitive series of over 23 coups between 1974 and the late 1990s, each involving varying degrees of violence.

No president in the history of the country has ever served their entire term. The military’s deep involvement in governing has caused a result of infighting and factionality, and has left the country bankrupt, with an almost non-existent state infrastructure.

There is no electricity grid in Guinea-Bissau and no power plant, which means no streetlamps, no traffic lights, major issues with telecommunications and banking, and a huge loss of productivity. At night, candles can be seen flickering in the windows of the mostly recycled-metal tin shacks housing ordinary citizens of Guinea Bissau, their only source of light after the sun goes down.

The buildings, mostly constructed almost half a century ago by Portugal, are rotting away in the steamy heat. Open sewers carry human waste and trash right in front of the doors of people’s houses, causing diseases like cholera to proliferate. There is also no functioning hospital, and GB’s medical service is so lacking that it relies entirely on grants from the Portuguese government to send severely ill patients to Portugal for treatment.

There is no real presence of law besides the military and their soldiers, not really a united army but factions of armed men who simply decide for themselves and by themselves what “law” is for Bissauans.

It is this grinding poverty and complete lack of caring by both the “government” and not even the slightest flicker of attention or recognition of existence from the outside world that has caused Guinea-Bissau to morph from unfortunate and ignored to becoming a massive issue for both Bissauans and the rest of the world: Guinea-Bissau has become the world’s first fully-fledged “narcostate”.

Since 2005, Guinea-Bissau has spiraled further down the path to complete anarchy. Attempts at presidential elections lead to the election of President Joao Bernardo Vieira, a career military man with many rivals, who was killed by soldiers a day after the targeted killing of another powerful army officer, General Tagme Na Wai. These events created a power vacuum, and this lack of authority created Guinea-Bissau’s present problem.

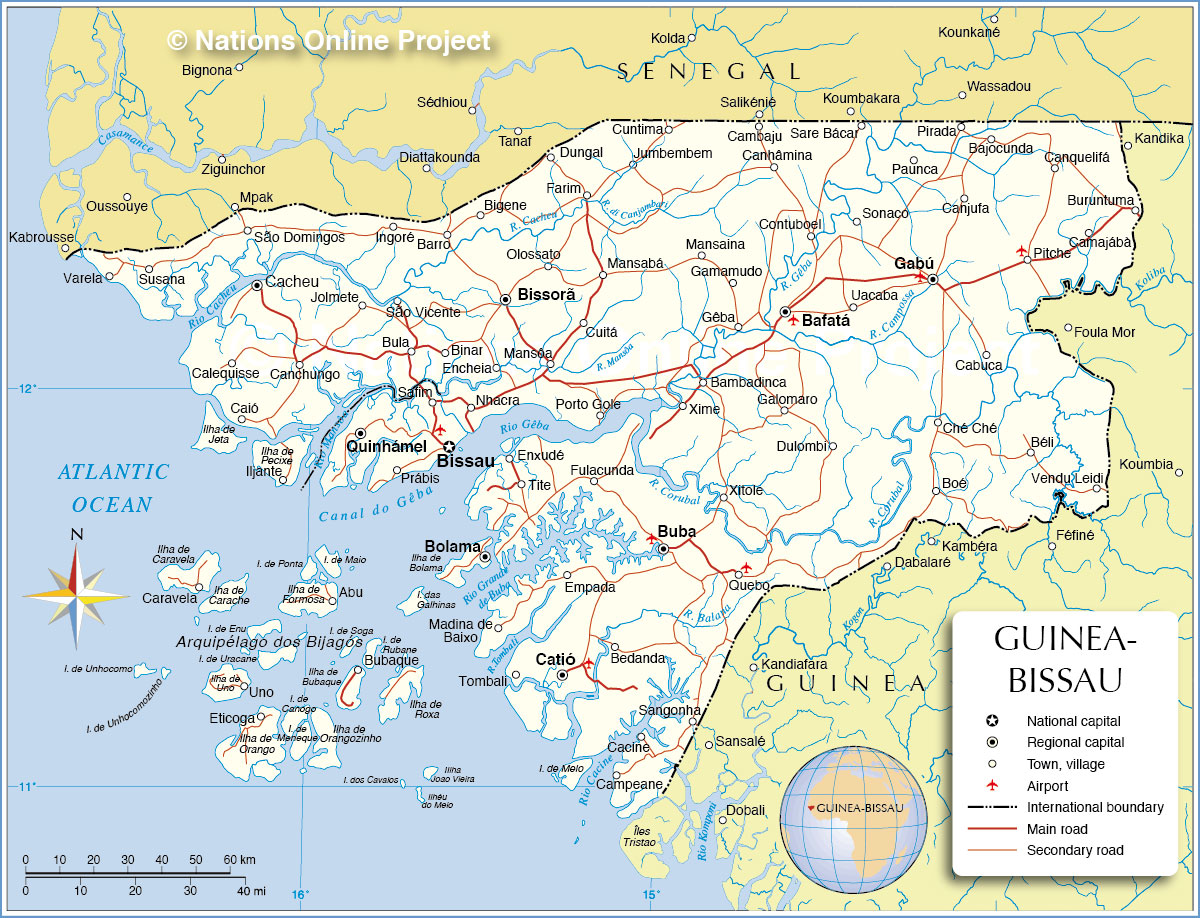

Even though geographically, it is tiny, Guinea-Bissau (GB for short) has a unique position on the Western coast of Africa, highly accessible by ship. GB also controls an archipelago of almost 90 islands, mostly uninhabited, sitting off the coast of the African continent in the Atlantic Ocean. Highly biodiverse, the Bijagos are mostly mangrove swampland, which makes them very hard to access if one does not know the terrain. This would become very important as a strategic advantage for Colombian drug traffickers, who began to exploit West Africa’s Atlantic coastline as a location for incoming drug shipments.

The traffickers made it a routine of paying off many different levels of the government officials of Sierra Leone, Liberia and Senegal, in order to bring in their produce of heroin and cocaine via cargo freighter.

Dealing with cash-strapped rebel armies from countries that were very rich in diamonds and desired their narcotics to embolden their soldiers in battle, Colombian cartels often exchanged their cocaine for uncut diamonds or weapons acquired by the rebel armies, which they would then trade with the largest rebel army in Colombia, the FARC. Once such a lucrative trade was revealed, many other criminal groups became involved, especially those who had easy access to large reserves of hard currency (like Israeli organised crime) or stockpiles of weapons (like the Russian mafia).

Only a very small percentage of the narcotics were consumed internally; the majority were brought from the cargo freighters to land in these war-torn countries, and flown by small plane to Europe (mostly to Spain) or brought to Nigeria, where they would be purchased by a global network of Nigerian drug smugglers, who would pay couriers to carry the narcotics internally (via swallowing) to Europe and America.

Once the Liberian and Sierra Leonean civil wars ended in the early 2000s, these operations were left without an easy entrance point to move their narcotics through West Africa. In Guinea-Bissau, things had become even more desperate. Colombian traffickers sensed opportunity and began approaching and systematically gaining control over any possible opposition to their plans using the power of their large reserves of money.

What would happen next is something unique: the complete and total degradation of a country to the point its’ main industry and primary function internationally becomes the trafficking of narcotics. This is very visible in this documentary, courtesy of the UK’s Channel 4:

This is Part 1 of “Guinea-Bissau, The World’s First Narcostate”. Part 2, the sequel, will be coming soon).

Sources:

http://www.fafo.no/pub/rapp/496/496.pdf

http://www.icij.org/project/making-killing/drugs-diamonds-and-deadly-cargoes

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-11799078

https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/Cocaine-trafficking-Africa-en.pdf

https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/investigate/organizedcrime/african